History of The Australian Labor Movement

Chapter 4. The War Exposes The Futility Of Reformism And Anarcho-Syndicalism

A. The Attitude Of The Labor Party Towards The War.

When war broke out in August, 1914, the Cook Liberal Government had already decided to hold a Federal election on September 15. It wanted to get rid of the Labor majority in the Senate and had precipitated a double dissolution on the question of preference to unionists. With the declaration of war the Labor Party proposed a political truce. W. M. Hughes and other leaders made public statements offering to withdraw from elections for the duration of the war if the Liberals would do likewise. The Liberal Party, however, felt confident that it would win the pending elections and consequently rejected Labor’s offer. It so happened that this confidence had no justification, for Labor was returned with a majority in both Houses and formed the new government, which was led by Andrew Fisher.

The parties were not at all divided on the question of the war. In the election campaign both sides made it clear that they fully supported the war aims of the Empire. The attitude of the Labor Party was defined in a Manifesto which stated:

“As regards the attitude of Labor towards the war, that is easily stated. War is one of the greatest realities of life and it must be faced. Our interests and our very existence are bound up with those of the Empire. In time of war half measures are worse than none. If returned with a majority we shall pursue, with the utmost vigour and determination, every course necessary for the defence of the Commonwealth and the Empire, in any and every contingency, regarding as we do such a policy as the first duty of the government. At this juncture the electors may give their support to the Labor Party with the utmost confidence.”

The whole history of the Labor Party, from 1891 to 1914, prepared it for the adoption of just such a policy. The other attitude could have been expected from a non-socialist, bourgeois liberal labor party. The Australian Labor Party, as we have seen, right from its very inception turned its back on the class struggle, rejected socialism and working class internationalism. The Objective of the party, adopted in 1908, was:

“a) The cultivation of an Australian sentiment based on the maintenance of racial purity and the development in Australia of an enlightened and self-reliant community.

“b) The securing of the full results of their industry to all producers by the collective ownership of monopolies and the extension of the economic functions of the State.”

Nothing could reveal more clearly than this Objective how far removed was the Labor Party from Socialism. The class divisions of modern society are overlooked; the independent class interests of the workers ace ignored; and for proletarian internationalism there is substituted bourgeois nationalism of the worst kind.

Lenin was completely justified in writing as he did in 1913 that:

“The Australian Labor Party does not even claim to be a Socialist Party. As a matter of fact, it is a liberal bourgeois party and the so-called Liberals in Australia are really Conservatives ... The leaders of the A.L.P. are trade union officials, an element which everywhere represents a most moderate and ‘capital serving’ element, and in Australia it is altogether peaceful and purely liberal.” [1]

The Labor Party’s attitude of support for the imperialist war therefore flowed logically from its whole outlook and practice in the preceding period. It is true that the Australian Labor Party was not affiliated to the Second International and consequently was not bound to the Anti-War Resolution adopted by that body at Stockholm, 1910, and at Basle, 1912. But this in no way lessens the guilt of these Australian labor leaders who betrayed the workers’ cause and led them into the imperialist war.

True to its election promises to do all possible to win the war for the ruling class, the Labor Party, within a month of its return to office, introduced two Acts which were to play a prominent part in the future life of the Commonwealth. These were the War Precautions Act and the Crimes Act. Both were ostensibly war measures, but, as we shall see, free use was made of them to curb militant working class activity and to railroad insurgent elements into gaol.

The overwhelming majority of reformist trade union leaders shared the official labor outlook on the war. Many of them hastened to show their patriotism, not by enlisting, but by sponsoring resolutions calling on their members to forego overtime rates and other privileges for the ‘duration’.

So far as the rank and file workers were concerned there was no marked enthusiasm for the war. At the outset they were confused and led astray by their leaders and for a time were deceived by the bourgeois propaganda that it was ‘a war for democracy’, a ‘war to end all wars’ and so on. Many were forced into the army by economic pressure, many more were enticed to join up by the fallacious argument that if the Empire were defeated Prussian militarism would overrun the world and thus put an end to all their hard won liberties. The workers were too immature politically to realise, and the Socialists were not in a position to make them, that there was another alternative, namely, the defeat of both British and German imperialism by the international working class. This path was mapped out by the Extraordinary International Socialist Congress at Basle November 24/25, 1912, whose Manifesto declared:

“If a war threatens to break out, it is the duty of the working classes and their parliamentary representatives in the countries involved, supported by the co-ordinating activity of the International Socialist Bureau, to exert every effort in order to prevent the outbreak of war by the means they consider most effective which naturally vary according to the sharpening of the class struggle and the sharpening of the general political situation.

In case war should break out anyway, it is their duty to intervene in favour of its speedy termination and with all their powers to utilise the economic and political crisis created by the war to arouse the people and thereby hasten the downfall of capitalist class rule.” [2]

The Bolshevik Party was the only party in the International which led consistently in accordance with the spirit of this resolution. Under Lenin’s slogan, “Turn the Imperialist War Into Civil War,” the Bolsheviks did, with all their power, utilise the economic and political crisis created by the war to arouse the people, and thereby brought about an end to the class rule of the landlords and capitalists in the great Socialist Revolution of November, 1917.

The only opposition to the imperialist war in Australia came from a few small groups of international socialists, who lacked any mass influence, and the Industrial Workers of the World. On the Sunday following the outbreak of war the I.W.W. unfurled a banner over its meeting in the Sydney Domain on which was inscribed the challenging query, “War, What For?” A forceful team of speakers proceeded to answer from the platform that it was a war for markets, a war for sources of raw material, a war for profits, a war in the interests of capitalism and against the interests of the working class. The I.W.W. continued to voice its revolutionary opposition to the war until it was suppressed under Hughes’ Unlawful Association Act in 1916.

In view of the important role played by the I.W.W. in the struggle against the war and conscription, and in view of the big influence which it exerted for a time in the Australian labor movement, it is well to digress here and elaborate somewhat on the history of this organisation.

B. The Programme And Activity Of The Industrial Workers Of The World.

The I.W.W. was founded in America in 1905 by the Socialist Labor Party, whose leader was Daniel De Leon. De Leon called himself a Marxist, but his knowledge of Marxism was far from complete. He was a good example of the type of labor leader referred to by Lenin as having mastered only certain aspects of Marxism, only certain “... individual slogans and parts of the new world conception, or demands ...” [3] The Socialist Labor Party was a most sectarian body which carried out propaganda for ‘pure socialism’ and held itself aloof from the struggle for immediate demands.

A Socialist Labor Party was established in Australia in 1897, which also based itself on the one-sided doctrines of De Leon, and, like its American counterpart, segregated itself from the masses. Some two years after the establishment of the I.W.W. in America the Socialist Labor Party here fostered clubs to spread the new doctrines of industrial unionism. These early I.W.W. Clubs were subordinated to the S.L.P., which exercised strict control over their activities. Many clubs chafed under this rigid control and felt that insufficient scope was allowed for developing their propaganda for industrial unionism.

In 1908 differences of opinion concerning the future relations between the I.W.W. and the S.L.P. led to a split in the American organisation. The adherents of De Leon wanted to retain affiliation with the S.L.P. and to continue under its political direction. The extreme syndicalist elements, led by Trautmann, would not accept this. They considered that industrial action should take precedence over political action, and that the I.W.W. should not be tied to any political party. The opposing factions came to be known as the Detroit I.W.W. (De Leon followers) and the Chicago I.W.W. (Trautmann supporters), taking these titles from the names of the towns which they made their headquarters.

It was the Chicago, or extreme syndicalist, wing which gained the ascendency here in Australia. In 1908 a Local was set up in Adelaide which secured a Charter from the Chicago body authorising it to act as the Continental Administration for Australia, with the right to issue Charters to new branches which might be formed in other parts. In 1913 the Sydney Branch, which received its original Charter from Adelaide, became the headquarters for the movement in Australia.

The principles of the I.W.W., as set out in the preamble to the constitution in 1905, were as follows:

“The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things in life.

“Between these two classes a struggle must go on until all the toilers come together on the political, as well as on the industrial field, and take and hold that which they produce by their labor through an economic organisation of the working class, without affiliation with any political party.

“The rapid gathering of wealth and the centering of the management of industries into fewer and fewer hands make the trade unions unable to compete with the ever-growing power of the employing class, because the trade unions foster a state of things which allows one set of workers to be pitted against another set of workers in the same industry, thereby helping to defeat one another in wage wars. The trade unions aid the employing class to mislead the workers into the belief that the working class have interests in common with their employers.

“These sad conditions can be changed-and the interests of the working class upheld only by an organisation formed in such a way that all its members in any one industry, or in all industries, if necessary, cease work whenever a strike or lockout is on in any department thereof, thus making an injury to one an injury to all.” [4]

Following the split in 1908 the Detroit faction disintegrated entirely and the Chicago faction remained as the I.W.W. It changed the set of principles adopted in 1905, by rejecting all mention of political action. The second paragraph of the preamble was altered to read:

“Between these two classes a struggle must go on until the workers of the world organise as a class, take possession of the earth and the machinery of production, and abolish the wages system.”

And two new paragraphs were added:

“Instead of the conservative motto, ‘A fair day’s wages for a fair day’s Work,’ we must inscribe on our banner the revolutionary watchword, ‘Abolition of the wages system.’

“It is the historical mission of the working class to do away with capitalism. The army of production must be organised, not only for the everyday struggle with capitalists, but also to carry on production when capitalism shall have been overthrown. By organising industrially we are forming the structure of the new society within the shell of the old.” [5]

By this action the I.W.W. became a purely industrial body, categorically rejecting even the necessity for a political party of the working class.

Concerning the methods of the I.W.W., Vincent St. John, its one time secretary in America, states:

“As a revolutionary organisation the Industrial Workers of the World aims to use any and all tactics that will get the results sought with the least expenditure of time and energy ...

“No terms made with an employer are final. All peace, so long as the wage system lasts, is but an armed truce ...

“The I.W.W. realises that the day of successful long strikes is past ...

“The I.W.W. maintains that nothing will be conceded by the employers except that which we have the power to lake and hold by the strength of our organisation. Therefore we seek no agreements with the employers.

“Failing to force concessions from the employers by strikes, work is resumed and ‘sabotage’ is used to force the employers to concede the demands of the workers.” [6]

The dogmas of the I.W.W. may be paraphrased and restated in a summarised form as follows:

a) There can be no peace in industry while capitalism lasts. Therefore, apart altogether from whether the objective conditions warrant it, the thing to do is to fan the flames of class war by strikes, sabotage, go-slow or any other means which present themselves.

b) Through the class struggle the workers will be brought together so that some day in some way they will spontaneously revolt and take possession of the means of production.

c) The concentration of production has rendered craft unionism obsolete. Therefore the craft unions must be supplanted by new industrial unions.

d) Sectional strikes have no value and should be dispensed with in favour of the general strike.

e) When the collapse of capitalism has been effected the new industrial unions will blossom forth as production syndicates, assuming the tasks of management in the new society.

It will be noticed that no consideration whatsoever is given to the question of the State – “The root question in all politics.” [7] The I.W.W. shared the opinions of the anarchists and anti-authoritarians, generally, on this vital issue. They regarded all forms of State power as being an abomination and thought that the rule of authority would be brought to an* end with the collapse of capitalism. They couldn’t conceive the need for the Dictatorship of the Proletariat in the period of transition from capitalism to communism.

Ridiculing the anarchists and their repudiation of politics, Marx wrote in 1873:

“If the political struggle of the working class assumes violent forms, if the workers set up their revolutionary dictatorship in place of the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, they commit the terrible crime of violating principles, for in order to satisfy their wretched, vulgar, everyday needs, in order to crush the resistance of the bourgeoisie, instead of laying down their arms and abolishing the State, they give the State a revolutionary and transitory form ...” [8]

“Engels enlarges on the same ideas in even greater detail and more simply. First of all he ridicules the muddled ideas of the Proudhonists, who call themselves ‘anti-authoritarians’, i.e., they repudiate every sort of authority, every sort of subordination, every sort of power. Take a factory, a railway, a ship on the high seas, said Engels – is it not clear that not one of these complex technical units, based on the employment of machinery and the ordered cooperation of many people, could function without a certain amount of subordination and, consequently, without some authority or power?

“... If the autonomists would confine themselves to saying that the social organisation of the future will restrict authority to the limits in which the relations of production make it inevitable, we could understand each other, but they are blind to all facts which make the thing necessary, and they hurl themselves against the world.

“Why don’t the anti-authoritarians confine themselves to crying out against political authority, against the State? All socialists are agreed that the State, and with it political authority, will disappear as the result of the coming social revolution, i.e., that public functions will lose their political character and be transformed into the simple administrative functions of watching over real social interests. But the anti-authoritarians demand that the political state should be abolished at once, even before the social conditions which brought it into being have been abolished. They demand that the first act of the social revolution shall be the abolition of authority.” [9]

The I.W.W. considered that the overnight ‘abolition of authority’ would leave the working class with purely economic functions to fulfil and that these would be carried out by the new industrial unions; hence, “By organising industrially we are forming the structure of the new society within the shell of the old.”

There were three main points in the I.W.W. creed which appealed to fairly wide sections of Australian workers:

1) the propaganda for industrial unionism;

2) the criticism of Wages boards and Arbitration Courts and

3) the denunciation of reformist union officials and labor politicians.

The workers were themselves becoming aware of the growing inadequacy of the craft unions in view of the rapid development of monopoly. They naturally lent a willing ear to any proposals designed to strengthen their ‘citadels’. The Wages Boards and Arbitration Courts had now been functioning long enough to reveal something of their true character, and workers generally were becoming fed up with the long delays associated with the ventilation of their grievances through the Courts. They were already beginning to contrast the meagre results obtained from arbitration with those achieved by direct action in an earlier period. Consequently they were in a receptive mood for the I.W.W. propaganda directed against the whole system. Finally there was the conduct of the Labor Party in office and its spineless subservience to the ruling class which turned many workers in the direction of syndicalism.

In 1914 there were four I.W.W. Locals active in Adelaide, Sydney, Broken Hill and Port Pirie, but its influence already extended far beyond its small membership. In evidence of this the Executive of the Melbourne Trades Hall Council was called on in 1907 to report on a proposal to reorganise the trade union on I.W.W. lines. The proposal was rejected but the I.W.W. itself was acknowledged to be “another phase of the unionist movement in which the distinctive badge of craftism is merged in the greater humanity ...” In the same year a Trade Union Congress was held in New South Wales and a resolution was put forward by the delegates from Newcastle recommending the adoption of the I.W.W. Preamble.

This met with considerable support, but it also encountered opposition from the craft union officials and aspirants for parliamentary honours who were present at the Congress. After considerable debate it was defeated. These initial setbacks did not arrest the spread of I.W.W. influence. In July, 1907, the coal miners in New South Wales and Victoria federated. Prior to this there had been three separate federations in the Northern, Southern and Western districts of New South Wales, as well as the Victorian organisation. The chief credit for bringing these bodies together into one Federation belongs to Peter Bowling, a miners’ leader and member of the I.W.W. In 1908 a strike took place among tramwaymen in Sydney and Holman, deputy leader of the Labor Party, claimed that the I.W.W. were responsible.

More evidence of the spread of I.W.W. influence was provided in 1909, when the Broken Hill miners went on strike. At the height of the struggle the leaders were arrested and charged with seditious conspiracy. Wade, the Premier, transferred the scene of the trial from the Barrier to Albury. This was regarded by unionists as evidence of the Governments intentions to secure a conviction by fair means or by foul. Feeling ran high in trade union circles and considerable support was found for the I.W.W. propaganda for a general strike. Peter Bowling moved in this direction at the Trade Union Congress which met in Sydney a few days before the trial was scheduled to take place. It was defeated by a narrow majority.

A few months later the coal miners came out on strike to rectify a number of outstanding grievances and again it seemed likely that the I.W.W. plans for a general stoppage would be realised. Peter Bowling exerted himself to bring this about. Negotiations were opened with the waterside workers as a first step in this direction. At this stage the Government intervened and proposed to the miners that they return to work pending a compulsory conference. This idea was rejected by the miners who continued the discussions with the wharfies with a view to extending the struggle.

In an attempt to intimidate the workers the Government caused Bowling and other strike leaders to be arrested and charged with violating the provisions of the Industrial Disputes Act. Under pressure bail was agreed to and they were turned loose. W. M. Hughes, who at the time was leader of the Waterside Workers’ Union, had one eye on the pending Federal elections in which he was a candidate, and was anxious to avoid becoming involved in the dispute. At the first available opportunity he broke off negotiations with the miners, who thereupon declared that they would continue the struggle alone.

This schism proved to be just what the Premier, Wade, had been waiting for. He immediately rushed through both Houses of Parliament a Bill to amend the Industrial Disputes Act. This new Coercion Act, or ‘Leg Iron Bill’ as it came to be known in union circles, placed strikes in certain specified industries in a special category and forbade them under severe penalties. Police were given exceptionally wide powers under this legislation and persons charged with offences against it were deprived of the right of trial by jury. No sooner was the ink dry upon the Governor’s signature of assent than Bowling and his colleagues were again arrested and thrown into gaol. This time bail was not allowed and the strike leaders remained in prison until they were sentenced to eighteen months’ imprisonment. Under these circumstances the strike soon collapsed.

This serious setback checked for a time the growth of the I.W.W. But with the outbreak of war it soon revived and began to make ever more rapid headway. Early in 1915 new Locals were established in Melbourne and Brisbane. In the following year branches were set up in Fremantle and on the Western Australian goldfields. Locals also sprang up at different centres in North Queensland. The I.W.W. was well on the way to becoming a nation wide organisation. Early in 1914 it began to publish a weekly newspaper, “Direct Acton,” which reached a circulation of 14,000.

The first lending article in this paper is most interesting. It not only offers a fair sample of the I.W.W. philosophy, but at the same time indicates how it was that the I.W.W. was incapable of providing the workers with a leadership alternative to the A.L.P.:

For the first time in the history of the working class movement in Australia,” this leader states, “a paper appears which stands for straight out direct actionist principles, unhampered by the plausible theories of the parliamentarians, whether revolutionary or otherwise ... (My emphasis. E.W.C.)

The I.W.W. thus rejected all parliamentary action. It made no distinction between reformist politics and revolutionary politics. This was one of the major theoretical weaknesses of the I.W.W. To reject politics entirely is to leave this sphere exclusively to the bourgeoisie, to leave them in undisturbed control of the State. The Australian workers had learned from their experience in the ’nineties just what this means, and had sought instinctively to overcome it by forming their own party.

The A.L.P. failed the workers, not because it engaged in parliamentary activity, but because, lacking in socialist principles, it raised this form of struggle to the level of an all embracing one sided, theory, and subordinated to it all other forms of the class struggle. This contributed to the A.L.P. sinking deeper and deeper into the bog of opportunism and to its coming more and more under bourgeois influences. The task confronting socialists was to rescue the workers movement from this swamp, to rid it of opportunism, to give it a conscious purpose and to reduce parliamentary action to its proper perspective as one of many (and not the most important) of the different forms of class struggle. The I.W.W. was theoretically and organisationally incapable of tackling this great task. It swung to the opposite extreme and rejected political action entirely. Thus, on spite of its revolutionary opposition to the war, it was unable to mobilise the Australian workers for a socialist way out.

Most of the propaganda and activity of the I.W.W. bears the same negative character as its attitude towards parliamentarism. It denounced craft unionism, it denounced arbitration, it denounced the Labor Party, etc. But the prosecution of the class struggle calls for much more than a bald denunciation of the evils of capitalism; it calls for constructive as well as destructive effort; it calls for ability to tackle and solve in a positive manner all the problems which con- front the labor movement at the different stages of its development. This is where the I.W.W. failed. Because of its own one-sidedness and sectarianism, because of its unsound theory it was unable to find a constructive answer to the difficult questions which history put before the Australian labor movement during the first imperialist world war.

The organisational structure of the I.W.W. reflected its unsound theoretical principles. On paper this scheme provided for six main production departments:

1. Agriculture;

2. Mining;

3. Transport and Communication;

4. Manufacture;

5. Construction;

6. Public Service.

Within these main departments room was left for industrial unions in the narrower sense. For instance, department 3 would be subdivided into unions for railwaymen, seamen, road transport workers and so on. These smaller bodies would have their own executive, which would be subordinated to the Department Executives. These in turn would be subordinated to the General Executive Council. These plans never emerged from the blue print stage of development. Only a mere skeleton form of organisation was actually created, with a General Executive in Sydney and a number of Locals scattered throughout the Commonwealth. Consequently the I.W.W. was not equipped to stand up to the political struggle which, notwithstanding its own doctrines, the State and Federal authorities forced upon it. When the leaders were arrested in 1916 the organisation was crippled. It attempted to carry on but lacked the necessary means. For a time “Direct Action” continued publication and Domain meetings were held as usual. But early in 1917 when a mass round up of members was carried out and Tom Barker and other leaders were deported the I.W.W. was finally crushed.

The I.W.W. was declared an illegal organisation in December, 1916, under the Unlawful Associations Act put through by the Labor Government of W. M. Hughes. But the twelve members, who had been arrested prior to this, were proceeded against by the Crown under the common law on trumped up charges of “conspiracy to commit arson and sedition.” They were sentenced by Mr. Justice Pring to terms of imprisonment ranging from 5 to 15 years. A vigorous campaign was launched among the working class, demanding their release. In 1918 a Royal Commission was appointed to investigate the case, but the twelve remained in gaol, the Commissioner, Mr. Justice Street, declaring that, “nothing could be done.”

However, organised labor showed that something could be done, and the sustained agitation resulted in a second Royal Commission being appointed in 1920. The new Commissioner, Mr. Justice Ewing, found that four of the Crown witnesses in 1916 were “liars and perjurers.” Three of them, David Goldstein, Louis Goldstein and Scully, were trying to gain immunity from prison in reward for their perjured evidence, while the fourth, McAlister, was himself a member of the I.W.W. and involved in a conspiracy to commit arson. “The conviction of the prisoners,” Mr. Justice Ewing said, “had perforce to depend to a very large extent upon the evidence of these witnesses.”

C. The Anti-Conscription Movement.

Early in 1915 the question of Conscription for overseas service came under discussion in Australia. Compulsory service for home defence was already on the Statute Book, Labor having been to the forefront in placing it there. As early as 1903 W. M. Hughes, supported by his colleagues, Watson and Spence, moved in Parliament for the adoption of compulsory military training. In the same year the Federal Parliament passed a Defence Act which empowered the Governor-General to call out the Citizen Forces for war service. This Act was amended in 1909 to render all male inhabitants between the ages of 18 and 60 liable to service in the Citizen Forces in time of war. In 1911 a Cadet system became operative for training boys between 14 and 17 years of age. A plan for adult training was scheduled to follow. A bitter controversy broke out around the principle of compulsion. Hughes and the main body of Labor leaders vigorously defended this principle and denounced its critics, who favoured voluntarism. The chief opposition to compulsory service came from small groups of socialists, who were opposed to all forms of militarism on grounds of principle, and religious sects like the Society of Friends.

The boys called up by the Act of 1911 were intensely hostile towards the system. Between July, 1911, when the compulsory training scheme began to operate, and March, 1915, there were no less than 34,000 prosecutions for refusals to attend drill. The unremitting socialist and pacifist agitation against the principle of compulsion in this period no doubt laid the basis for the organised opposition to Conscription which developed in 1916.

In February, 1915, the Australian Defence League, a bourgeois patriotic association with which Hughes and Holman were intimately connected, urged the Commonwealth Government to “draft the men of the nation for war and defence.” By July the leaders of various Chambers of Commerce and Chambers of Manufacturers had joined the clamour for Conscription. On the other side the adherents of No-Conscription became equally vocal.

The I.W.W., which had already taken up an attitude of opposition to the war, seized upon the public utterances of the Conscriptionists to further its own cause. In Melbourne the Australian Peace Alliance was formed, which, in addition to opposition to Conscription, advocated peace by international arbitration. A No-Conscription Fellowship was also set up, consisting of young men of military age who pledged themselves to undergo imprisonment rather than serve in the war. All over the country the pros and cons of Conscription were being debated.

In July, 1915, the Commonwealth Government passed a War Census Act, which the No-Conscriptionists rightly anticipated to be the first practical step towards compulsory overseas service. In the same month the Barrier Amalgamated Miners’ Association passed a resolution against Conscription. From then onwards the Unions and Labor Leagues began to take a more active interest in developments. In November, Hughes, who had succeeded Andrew Fisher as Prime Minister, promised the British Government another 50,000 men from Australia. Questionnaires and War Census cards were distributed to seek out eligibles in the community.

Unionists became alarmed at this turn of events and a deputation from the Brisbane Industrial Council waited on Hughes to elicit information concerning the Government’s intentions. Hughes was very evasive in front of the deputation, which was compelled to leave without getting much satisfaction. The War Census Cards were distributed, but, acting on the advice of their unions, 180,000 workers failed to fill them in, which nullified the whole scheme.

Up to this stage the Anti-Conscriptionists hadn’t succeeded in arousing much enthusiasm for their campaign. Their meetings were often poorly attended and were sometimes disrupted by gangs of drunken hooligans and small groups of misguided soldiers who were inspired and encouraged by the Conscriptionist press. But in January, 1916, Conscription became law in Britain and in consequence received more prominence in Australia. The Melbourne Trades Hall Council convened a special Conference in May to define the attitude of Victorian Trades Unions towards Conscription. It also debated a Resolution to send fraternal greetings to the workers in every country, imploring them to take action to force their governments to pronounce themselves openly on terms for peace. This important resolution, to which we will return later, was only defeated by the Chairman’s casting vote. The Easter Conference of the N.S.W. Labor Party pledged itself to fight against Conscription, but simultaneously pledged itself to support Hughes’ effort to raise an additional 15,000 troops by voluntary enlistment. The Victorian Labor Party Conference and the Hobart Trade Union Conference also carried resolutions opposing Conscription. On all sides the Anti-Conscription movement began to gain ground.

Following on a big pro-Conscription meeting staged by the Universal Service League in the Sydney Town Hall, the No-Conscriptionists organised a mass rally in the Sydney Domain. A real united front was brought into existence, and this became the chief contributing factor to the ultimate success of the “NO” campaign. The following organisations were among those to send speakers to the Domain meeting: The I.W.W., the A.W.U., the Trades and Labor Council, the A.L.P., the Australian Freedom League and the Australian Socialist Party. Although it would seem that no formal pact or agreement was entered into the united front was none the less constituted in practice. These organisations were normally separated by wide differences of opinion concerning ultimate aims and the methods of struggle to be employed in bringing about their realisation, and yet they found it possible to combine temporarily in a common struggle against the specific menace of Conscription. The fact that such diverse trends as socialism, reformism, syndicalism, trade unionism and pacifism were able to unite so effectively on this issue is of the utmost significance for the whole labor movement.

It disposes of the reformist fable that the united front is merely a latter day tactic of the communists for furthering their own ends. It proves beyond all doubt that differences on general questions of principle do not constitute an insurmountable barrier to common action on matters effecting the immediate interests of the working class. Each speaker from the Domain platform attacked Conscription from the viewpoint of his own particular organisation and the general effect was to greatly consolidate the “NO” forces. From then on the struggle became much sharper. The ruling class provoked larrikins and soldiers into attacking No-Conscription meetings. A biased and vicious censorship was operated against the anti-conscriptionist press, while civil and military police frequently raided socialist and trade union premises to seize documents and literature. This provocation led to the formation of a working class volunteer army at Broken Hill to combat Conscription and to defend the elementary rights of trade unions.

Hughes, who was still in London, had so far not committed himself definitely either way. On the one hand his long association with the Australian Defence League and his ardent support for the principle of compulsory military training in the past, led the Conscriptionists to believe that he would be wholeheartedly on their side in the struggle.

On the other hand, the No-Conscriptionists, recalling his unambiguous declaration of July, 1915, when the War Census Bill was under consideration, that, “In no circumstances would I agree to send men out of the country to fight against their will,” were equally certain that Hughes would be in their camp. “Pros” and “Antis” alike eagerly awaited the return of the Prime Minister to bring matters to a climax.

Hughes arrived back in July. The leading organ of the No-Conscriptionists, the “Worker” greeted his return with streamer headlines on the front page, “Welcome Back to the Cause of No-Conscription.” But Hughes, who was even then determined upon Conscription, would make no public statement on the issue until he had consulted Caucus. He soon discovered that most of his colleagues in the Labor Party were aware of the anti-conscription sentiment among the rank and file and consequently were not prepared to risk their political scalps by supporting the legislation which he had in mind.

For a time Hughes was in a quandary. It was conceivable that a Conscription Bill could be, forced through the Lower House with the support of the Liberals. But there still remained the insuperable obstacle of a Labor controlled Senate with a No-Conscription majority. Ultimately he sought a way out by means of compromise and made a proposal that a Referendum be taken for or against Conscription. In the campaign Labor members were to be free to take whichever side they pleased. After the ballot all would return to the Caucus fold, shake hands and agree to accept the people’s verdict. The object of this proposal was to avoid if possible a split in the Party which would jeopardise the life of the Government and bring to an abrupt conclusion Hughes’ career as Prime Minister. It was a typical opportunist attempt to find a solution to a difficult problem. It avoided the need for an immediate showdown and thus won the support of all members of Caucus. Hughes at the time was apparently quite confident that his Conscription proposals would be carried at the Referendum.

On, August 30 the first official announcement about the coining referendum was made. On September 1st, Hughes attended a meeting of the Executive of the Victorian Labor Party. He harangued this body for three hours in a vain attempt to convert members to his point of view. Undismayed at their adverse decision, Hughes hastened to Sydney to convert the N.S.W. Executive. He met with no greater success. By 21 votes to 5 the meeting rejected his proposals that they should support Conscription. The Queensland Executive, without even bearing the Prime Minister, arrived at a similar decision to New South Wales and Victoria. Not only did the New South Wales Executive refuse to support Conscription, it went further and rejected the idea that the politicians should be granted freedom of action on the matter. It demanded that they subordinate their will to that of the movement as a whole and come out openly and actively against Conscription. Hughes and a minority of his colleagues in the Federal Party ignored this edict and continued their activity in support of a “YES” vote. In N.S.W., Holman, who had replaced McGowan as leader of the Party and Premier of the State, was known to support Hughes. This attitude was shared by the majority of Holman’s Cabinet Ministers. In Queensland, while there were many Conscriptionists in the Party, they were not in a majority and submitted to the Caucus decision to oppose the Referendum and Conscription.

On September 15 the New South Wales Executive expelled Hughes from the Party and withdrew the endorsement of Holman and three other members of the State Parliamentary party at the pending elections. The remaining politicians were circularised and all who did not agree to oppose Conscription were dealt with in like manner. Holman and a majority of the Cabinet in New South Wales revolted against this attempt to bring them under the discipline of the movement and were ultimately expelled. Durack became the leader of the Party in New South Wales and Holman and his supporters went over to the Liberals and helped form a National Government in October, 1916.

The announcement that a Referendum was to take place was the signal for renewed activity on the part of “Pros” and “Antis” alike. The former had all the advantages of solid financial backing, free access to public halls and the full support of the capitalist press. The latter were not only denied these privileges but were further handicapped by a class biased censorship and numerous other restrictions imposed under the War Precautions Act. Nevertheless they struggled on until public sentiment began to change in their favour. Every means of intimidation and coercion against the anti-Conscription forces were resorted to by the Government. Hughes drafted a special War Precautions Act Regulation, whereby any intending voter at the Referendum could be interrogated as to whether he was subject to, and had obeyed, the proclamation calling up single men for home defence. The Regulation was only withdrawn on the eve of the ballot, after two labor members had resigned from the Ministry in protest against it. All Hughes’ machinations were in vain. When the poll was taken on October 28, Conscription was rejected. The “NO” vote totalled 1,160,033 and the “YES” vote 1,087,557.

When all the circumstances are considered the defeat of Conscription was a tremendous victory for the democratic forces in Australia, and in the first place for the labor movement. The result of the Referendum showed that whilst the workers and the middle classes were deceived about the real character of the war, and for the most part were not actively opposed to it, they were not so far carried away by chauvinism that they were prepared to sacrifice the last vestiges of democratic rights upon the altar of militarism.

The Conscription struggle had a profound effect upon the Labor Party. The developments in New South Wales have already been touched on. Holman and Co. were expelled. Similar happenings occurred in the Federal sphere and in other States, with the exception of Queensland, where there was no split. When the Federal Parliament reassembled after the defeat of the Referendum Hughes was admitted to the first meeting of the Labor Party Caucus. But it was only to hear a motion of no confidence moved against him. Refusing to listen to any debate Hughes stalked out of the meeting, calling on his followers in the Referendum campaign to do likewise. Twenty four members followed Hughes out of the Party meeting, while forty remained to carry the censure motion. Hughes formed a new Cabinet from the ranks of the renegades which was kept in office by the Liberals for a short time. Subsequently, however, Hughes emulated Holman and went over openly into the anti-labor camp, coalescing with the Liberals to form a Nationalist Party.

The No-Conscription struggle provided rich experience which helped to further advance the revolutionary education of the Australian working class, although, like the experiences of the 1890 strike, its full lessons have been but slowly mastered. It showed that on the one hand the masses were becoming more and more opposed to having their interests subordinated to the interests of the imperialist bourgeoisie, while on the other hand they were not yet sufficiently advanced to adopt the measures necessary to overcome this position. It showed up more clearly than ever the degree to which the leaders of the labor movement had become saturated with bourgeois ideology. The Conscriptionists like Hughes and Holman thoroughly exposed themselves and were driven from the movement. However, many of those who remained were no less opportunist, as their continued support for the imperialist war demonstrated. Some of them were subsequently unmasked in the years of the economic crisis, some of them continue the masquerade to this day.

The shortcoming of the Anti-Conscription campaign was that it remained a movement directed against only one aspect of the imperialist war and did not develop into a mass struggle against the war as a whole. Only a few members of the various socialist groups and the I.W.W. understood the connection between the struggle against Conscription and the struggle against the whole imperialist war. The I.W.W. participated in the campaign not merely with the object of defeating Conscription but to arouse mass hostility to the reactionary war. Its gross sectarianism, plus the ideological and organisational weaknesses mentioned earlier, prevented the I.W.W. from realising this revolutionary aim. Consequently the struggle against Conscription never grew over into a real antiwar movement which might have brought the working class on to the correct revolutionary path. This was just one more penalty paid by the Australian labor movement for its isolation from scientific socialism.

Mention was made in an earlier section of the Peace resolution introduced at the Melbourne Trade Union Congress in 1916. The Perth Conference of the Labor Party carried a somewhat similar resolution in 1918. The sentiments expressed in these resolutions, calling on the workers to bring pressure to bear on their respective governments to restore peace, provides further evidence of the backwardness of socialism in the Australian labor movement at this period.

The “Peace Slogan,” Lenin once wrote, “is meaningless unless it is accompanied by a call to revolutionary action against the imperialist war. It can only have the effect of throwing dust in the eyes of the workers, instilling in them false hopes that a democratic peace can be obtained without first overthrowing the imperialist government. The only slogan for revolutionary socialists in an imperialist war is to transform it into a civil war, into a fight for socialism.” [10] There is no evidence of any group in Australia having taken up and consistently advocated without any deviation such a policy. The I.W.W. and certain socialist sects may have come close to so doing at times, but for the reasons already stated, these bodies were not capable of rising to the necessary heights demanded by history. They did, however, pave the way for the development of a real Leninist Party in the post-war period.

D. The 1917 General Strike.

A second Conscription Referendum was held in 1917 and this time the “NO” majority increased to 166,588. But an event which overshadowed in importance the second Anti-Conscription campaign was the general strike which took place in New South Wales. Right on the heels of the first No-Conscription victory the New South Wales coalminers staged a very well organised strike for the eight hours bank to bank shift and an increase in wages. The success of the miners had a big influence on other unions and the I.W.W. propaganda for a general strike gained ground.

By this time discontent was becoming fairly widespread. Wartime profiteering, high food prices, long hours and speed-up methods in production, plus the refusal of the Arbitration Courts to increase wages sufficiently to offset the increased cost of living were the chief causes of industrial unrest. New South Wales, as the most highly industrialised State, was naturally the most effected.

From the beginning of 1913 to the end of the first quarter of 1916, New South Wales experienced 729 industrial disputes, involving a loss of 2,078,934 working days and £1,072,905 in wages, whereas, in the rest of Australia there were but 308 disputes causing a loss of 656,096 days, and £339,079 in wages.[11] Since the outbreak of war the cost of living had been steadily rising. By July, 1917, on the eve of the general strike, it was 30% or more above the pre-war level. The price of meat had gone up 62.5% and the prices of other foodstuffs and groceries 22.6%. The total combined average increase was 32.6%.[12]

Over the same period the living wage had only increased by 15.6% (In February, 1914, it was £2/8/- per week. In December, 1915, it was raised to £2/12/6, and in August, 1916, it was further increased to £2/15/6. It remained at this level until September, 1918, when it was raised again to £3)[13]

These figures indicate that the workers suffered a reduction of approximately 15% in real wages in the first three years of the war. But in actual fact their loss was even greater. If average weekly wages, and not the declared living wage, is taken as the basis for comparison, the reduction in real wages approximated 21%. (At the end of 1913 the average weekly wage in New South Wales was £2/15/9. By the end of 1916 it had risen to £3/1/11)[14] This represents an increase of 11% and since the cost of living had increased by 32.6% the drop in real wages was 21.6%.

The reason for the percentage increase in the average weekly wage being less than that of the declared living wage was that many skilled and semi-skilled workers had their margins reduced. The Arbitration Court began in this period to apply the rule of the “Diminishing scale of increases in ratio above the minimum wage,” i.e., as one judge expressed it, “In times like these the higher classes of worker can no longer claim, as a right, the same proportion above the minimum as prevailed before the war; all must bear their share, but those must bear most who are able to bear most.” [15] In various judgments, where the living wage question was involved, the Court recognised that a tremendous increase in the price of necessities had taken place, but it steadfastly refused to increase wages by a proportionate amount. It held that, the war had created an abnormal set of circumstances which justified a departure from the old principles of wage fixation based on the cost of living, and the workers would have to adapt themselves to a lower standard.

This view was first expressed by Mr. Justice Powers, and later approved by Mr. Justice Higgins. It is quoted in the judgment of the N.S.W. Court of Industrial Arbitration in its Inquiry into the cost of living and the minimum wage:

“I recognise that people cannot live in these days in reasonable comfort on the living wage prescribed, if they attempt to maintain the same regimen as in the days before the war and drought. If clothing goes up in price, ordinary people are more careful of what they possess and of new purchases. If butter goes up to a high price, other things are used in its place. If meat goes up in price less is used, etc ...” [16]

It was held out to the workers that this necessary adaptation to a lower living standard would be their contribution to the sacrifices which were expected from all sections in the community in the interests of winning the war. However logical these arguments may have seemed to the judges they failed to convince the workers. The latter saw employer after employer doubling his profits, company after company raising its dividend rates, and couldn’t escape the feeling that the sacrifice was altogether too one sided.

Figures like the following, which appeared from time to time in the financial columns of the daily press, added fresh fuel to the smouldering fire of working class discontent. Adelaide Steamship Company increased its profits from £4 000 in 1915 to £77,500 in 1917, and raised its dividend from 6% to 10%. Huddard Parker increased its dividend rate from 7 to 10%. Broken Hill South raised its dividend from 15% to 120%. Broken Hill North from 5% to 40%. Goldsborough Mart from 10% to 15% and Farmer & Co., also from 10% to 15%.

It only needed a slight puff of wind to fan the glowing coals of working class anger into a white hot blaze. This was provided, it will be seen, by the attempt of the Railway Commissioners to introduce a speed up system into the Randwick Workshops in July, 1917. This became the immediate cause of the general strike which flared up in August.

An upward tendency in the strike movement was manifest in the period preceding the outbreak of war. This upswing began in 1912 and continued during the next four years. The year 1914 was marked by a particularly sharp rise in the number of strikes, the number of workers involved and days lost through stoppages. The following table gives a clear picture of these developments. [17]

Commenting on these figures, the Industrial Gazette states:

“The number of dislocations reached its maximum in the year 1908. In each succeeding year the numbers decreased consistently until 1911. An upward tendency made itself apparent since the beginning of 1912. These fluctuations reflect fairly the industrial history of the State; its comparative prosperity from 1908 to 1910 temporarily checked by the general coal strike in 1909-10; the recovery of trade in recent years, and with it the corollary to prosperity, renewed efforts of the workers to share in the betterment of conditions.” [18]

From the foregoing it can be seen that the war broke out at a time when the workers were already beginning to struggle for an increased share in the prosperity of the country. The coal miners it would seem, were in the vanguard:

“The extraordinary increase in the number of dislocations in 1914 was contributed to in the main by the coal and shale mining industry. During 1914 a greater degree of unrest prevailed in the coal industry than for many years. In no year since the general strike in 1909-10 had so many working days been lost.” [19]

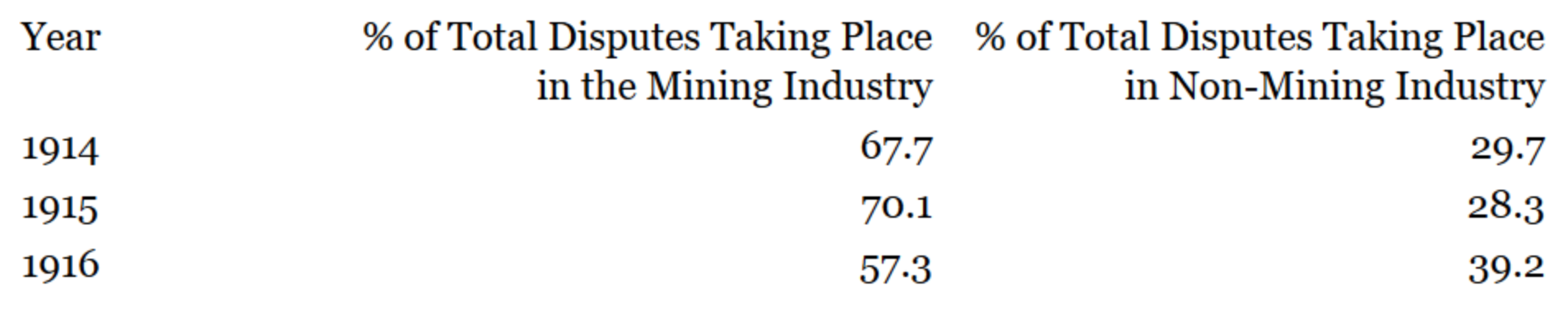

The preceding table of disputes shows that this unrest persisted during 1915/16. In November, 1916, it culminated in the successful strike for the eight-hour bank to bank shift and a 20% wage increase. From the same table it can also be observed that the mining industry accounted for the greater proportion by far of all the disputes taking place. From July, 1907, to December, 1913, the mining industry actually accounted for two-thirds of the total number of dislocations, three-quarters of the total number of workers involved, and nearly nine-tenths of the total working days lost. [20] A large number of these stoppages were local in character and short in their duration. They were caused mainly by disputes arising from the coal owners violation of local customs and working conditions.

A significant factor which emerged towards the end of 1916 was that unrest in non-mining industries was becoming far more widespread, as the following table reveals:

Questions arising from wages and hours provided the chief causes of disputes, except in the case of the mining industry, where, as already mentioned, local customs and working conditions gave rise to most of the friction. But even in the coal mining industry the major dispute, which occurred in November, 1916, centred around wages and hours.

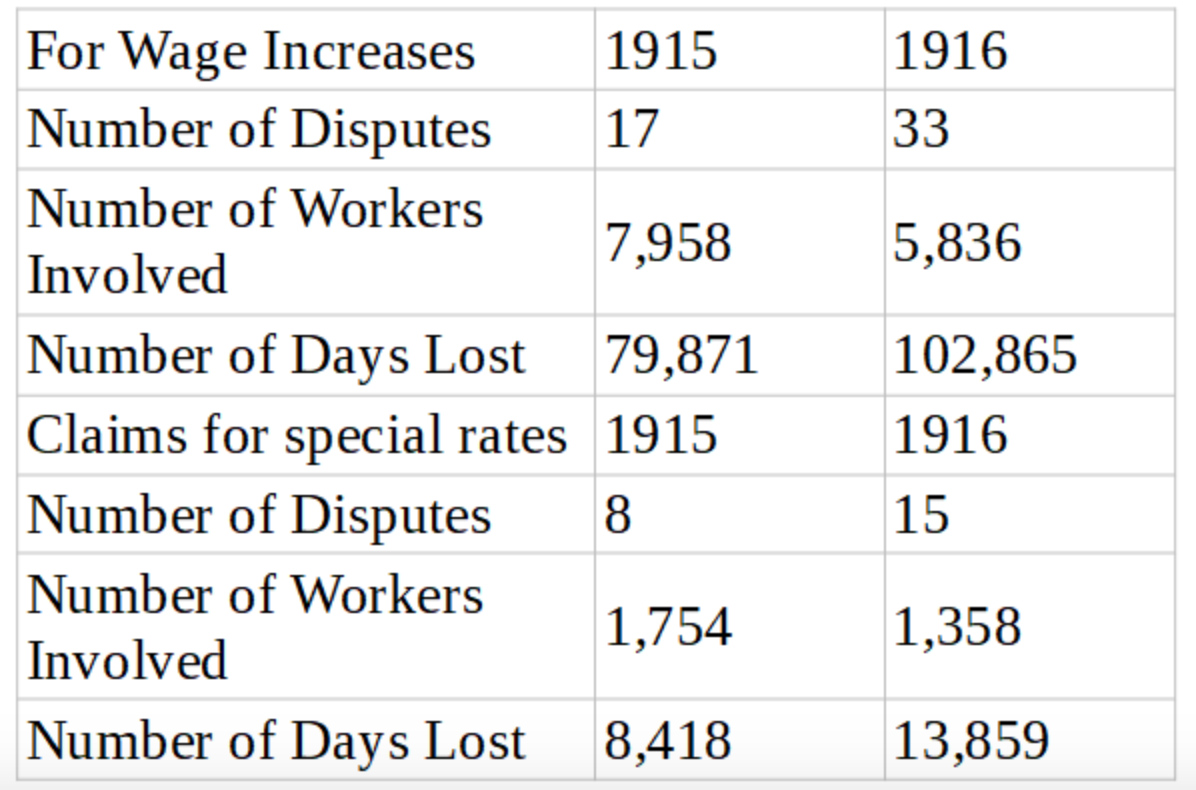

In the non-mining industries, as the cost of living mounted so did the number of disputes concerning wages grow. In 1914 wages demands accounted for 21% of the total number of stoppages. In 1915 the percentage advanced to 29, and in 1916 to 39.6. In the latter year there was a particularly marked rise in the number of stoppages arising from demands for increased wages and special rates, as the following table shows:

Such was the general picture of events leading up to the big strike which broke out in August, 1917. Since 1913 there had been fairly widespread criticism of the New South Wales Labor Government among the trade unions for its failure to implement any of the important planks in its platform. During the regime of this government, from the end of 1913 to November, 1916, the politicians and reformist union officials had great difficulty in restraining the workers from struggle and holding their militancy in check. A sidelight on their problems in this regard is revealed in a statement issued by W. Ainsworth, the Secretary of the Loco. Enginedrivers’ Association, during the big strike. “For months now,” he said, “my executive has been faced with the spirit of unrest and discontent. Personally, I have endeavoured, and I have used my hours of recreation for the purpose of allaying the troubles that were so evident ...” When the Labor Party split on the Conscription issue and Holman was expelled, he linked up with Wade to form a Coalition Ministry. At the elections, early in 1917, the newly formed “National” Party was returned to office. It now became more difficult than ever for the reformists to hold the workers back.

In June, 1916, the Chief Commissioner of Railways and Tramways bad introduced a time card system in the Randwick Workshops. The employees objected to this on the grounds that unreasonable speeding up of the labor process would follow. After a series of conferences between union officials and the Government the system was withdrawn. The Union claimed that the Government agreed that no further changes in the conditions of labor would be brought about during the war. On the other hand the Railway Commissioner claimed that the cards were only withdrawn temporarily until the system could be improved. In any case the cards made their reappearance in July, 1917, within a month or so of the return of the newly formed National Party. Holman, the leader of the party, was absent in England and Fuller was the Acting Premier.

On July 27 a mass meeting of members of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers, who were effected by the card system, was held in Sydney Trades Hall and it was decided not to work while the system was in force. On July 28 the officials of the A.S.E. conveyed this decision to the Commissioner. On July 30, E. J. Kavanagh, Secretary of the Labor Council, announced that, in view of the position which might arise, a joint meeting would be held that night of the representatives of the various Railway Unions and the Executive of the Labor Council. On the afternoon of July 31, a joint deputation of Labor Council and Union representatives interviewed the Commissioner and were told that under no circumstances would the card system be withdrawn. On the same night the delegates from the fourteen different Railway Unions assembled at the Trades Hall to hear the report of the deputation.

When informed of the uncompromising attitude of the Commissioner the meeting carried a resolution to deliver an ultimatum that unless the card system was withdrawn by Thursday, August 2, the whole of the unions concerned would stop work. On August 1, Kavanagh again saw the Commissioner and put before him the Unions’ ultimatum. Later in the day the Commissioner replied by letter, reaffirming his refusal to withdraw the cards. On the same day Fuller made a statement in Parliament upholding the attitude of the Commissioner. He also claimed that there was no intent on the part of the Commissioner or the Government to speed the men up and that if necessary a public inquiry would be held after the card system had been given a three months’ trial.

It seems that among the unionists concerned there was some confusion about the real meaning of the ultimatum, although the terms of the motion itself were quite clear:

“That we re-affirm the resolution carried at Monday’s meeting that an ultimatum be issued to the Government that unless the card system is withdrawn by next Thursday, August 2, the whole of the unions concerned will stop work.”

The unions represented at the meeting which carried this resolution were: The Amalgamated Society of Engineers, Australasian Society of Engineers, Boilermakers, Blacksmiths, Electrical Trades, Plumbers, Sheet Metal Workers, N.S.W. Govt. Tramways Employees’ Union, Amalgamated Rail and Tramway Service Association, Moulders, Carpenters, Timber Workers, Ironworkers, Coachmakers, and Metal Polishers. The resolution didn’t state whether all of these unions would stop work, or whether “the whole of the unions concerned” referred only to those directly effected by the card system. Apparently the latter was the case. It also appears that no steps were taken to inform the rank and file what they were expected to do in the event of the ultimatum being rejected. It seems, from what subsequently transpired, that it was left to them to act on their own initiative in carrying out the terms of the resolution. The union leaders knew full well, from the terms of the Commissioner’s letter and from Fuller’s statement in the House, that the card system would not be withdrawn. They should therefore have given clear instructions to their members about the stoppage which was scheduled for August 2. Instead of which the 1300 employees at Randwick went to work as usual at 7.30 and only ceased work at 9 a.m. when the members of the A.S.E. found that the card system was still in operation. About 3000 employees in the Eveleigh Railway Workshops also stopped work. Small groups of employees of various categories in other workshops and depots followed the lead of the Randwick and Eveleigh men. The total number of men usually employed in all these shops was 5,700. By the end of the day 4673 were on strike, while 1027 remained at work. Figures released some time later showed that the total number of men who came out in all departments on August 2 was 5780, while the total number within the potential range of a general rail and tram strike was about 42,000.

Late in the afternoon of August 2, a hastily convened conference of delegates from the fourteen unions likely to be involved was held in the Sydney Trades Hall. This meeting failed to formulate any concrete plans for handling the dispute. Hopes were still entertained that a last minute compromise could he arranged. In contrast to the indecision of the strike leaders was the prompt action of the Railway Commissioner who at once issued instructions reducing the speed of all trains and trains and curtailing services. This should have convinced the unions that the Government really meant business.

On August 3 a number of Enginedrivers, Cleaners, Moulders, Boilermakers and others were drawn into the dispute. Acting Premier Fuller heaped more fuel on the gathering blaze by a provocative public statement defining the Government’s attitude.

“There are in this State,” he alleged, “a limited number of men who for the time being are in control of several trade unions and who have lost all sense of patriotism and responsibility and are deliberately contributing to the success of the enemies of civilisation by their actions.”

This pro-German bogey was used extensively by Fuller throughout the strike to discredit the leadership. But not only was suspicion cast upon the motives of the leaders, the intelligence of the rank and file was insulted. “Nine-tenths of the men do not know what the strike is really about,” Fuller claimed, “they are being blindly led into this appalling conflict by a few dangerous leaders.”

Actually the reverse was the case. The workers, driven beyond endurance and smarting under many grievances, were spoiling for a fight and were pushing their leaders into action. The latter, reduced to flabbiness by long years of peaceful Arbitration Court practice, had no stomach for the battle. They constituted a greater menace to their own members than they did to the Government. Fuller again intimated that the Government was still prepared to hold a public inquiry after the card system had been in operation for three months. But there would be no compromise, the men would have to return to work on the Government’s own terms. Making a bid to win public support for the Government and to turn middle class sentiment against the strikers, Fuller concluded his statement with the peroration:

“The time has come for the people of this State to take a stand against those extremists who have for a long time been deliberately conspiring against public interest and who have been responsible for the industrial ferment which has disgraced this State from the beginning of the war. There is yet time to avoid a bitter struggle. The door is still open to reinstatement of sensible men. This door will be closed to many if they persist in their present attitude.”

Inherent in this statement is the threat to rid the Railway and Tramway services of “troublesome” elements who stood up for their rights, and to smash the existing unions, replacing them with subservient bodies of the company union type if they failed to curb these progressive elements. Later we shall see the lengths to which the Government was prepared to go in carrying out this threat.

E. J. Kavanagh, on the same day issued a statement on behalf of the Unions’ Defence Committee. This document shows the light in which the leaders viewed the struggle and their own tasks. Like the title assumed by the Strike Committee, it reveals how far the minds of the people in control were dominated by the paralysing notions of “defensive strategy” and, concomitant with it, compromising tactics.

“The Defence Committee has been appointed with the object of carrying on negotiations for a settlement of the dispute.” Such was the introduction to the Manifesto. The agreed basis for a settlement, it continued, was:

1. The Railway Commissioners to revert to the position as it existed on June 1.

2. The Government to grant a Royal Commission to enquire into the subject matters of the trouble.

3. That the men return to work upon the granting of this.

Kavanagh concluded his statement on behalf of the Committee with expressions of fear of “what might eventuate if a speedy settlement was not effected ... There was a possibility of the trouble extending throughout the whole rail and tram service ... Private employers must eventually be effected to a degree ... He had never known a body of men so determined and unanimous, etc.” Any hopes which the strike leaders entertained that the Government would be moved to compromise by such a “terrifying” prospect were without foundation. Fuller’s statement should have made it clear that only a very real and not a sham fight would bring success to the strikers. The leaders from the beginning had no intention of mobilising the workers for such a struggle, they hastened to assure the Government and the public at large that there was “no extreme socialism behind the dispute.”

On August 5, with several of their members already on strike, the Loco. Enginedrivers, Firemen and Cleaners’ Association and the Amalgamated Rail and Tram Service Association met and decided officially, to cease work. On August 6, Kavanagh, in the name of the Defence Committee, declared all coal in the hands of the Railway Commissioner “black,” and stated that the decision of the Loco. men and the A.R.T.S.A. meant that all rail and tram services would cease at midnight. But the weaknesses of craft and dual unionism resulted in a number of unionists not covered by these organisations remaining at work. Rail and tram traffic was severely crippled but not completely paralysed. Emergency measures were adopted by the Commissioner and the Government to operate a skeleton service.

Forty suburban trains came into Central and thirty-four went out, as against 660 normally. Sixty trams each with an escort of two policemen, operated in Sydney to take people home from work. The Railway Commissioner issued a further statement threatening victimisation to those who remained out on strike. The Government also made another pronouncement, claiming that,

“We are now dealing with what is in effect a rebellion against the orderly government of the country ... The Government makes a final appeal and gives every employee a chance to return to work by Friday, August 10. At the end of three months an enquiry will be held into the card system. After Friday none will go back on the old status. Strikers will be punished and loyalists will be rewarded. Volunteers will be enrolled.”

By this time the hold up was beginning to affect coal miners, metal workers, carters and drivers and other sections of the working class.

On August 7, the fifth day of the strike, eighteen unions and some 30,000 workers were already involved. Of the wages staff in the employment of the Railway Commissioners, 17,348, or 61% were on strike, while 10,819, or 39% were still at work. The confusion which marked the calling of the strike in the first place had not yet been overcome. Nor was it at any time cleared up during the course of the stoppage. There was a lack of unity and understanding among the craft unions involved. Where a clear call to strike action was given few unionists disobeyed their organisation. The number of such remaining at work would have been even fewer had more vigorous steps been taken by the leadership to clearly explain the issues involved. Fuller availed himself of this situation and sought to compound the confusion. He accused certain union executives of violating the rules of their organisation by ordering a strike without first conducting a secret ballot. “The men’s hearts are not in the fight,” he alleged, “they just don’t like being called scabs, but the Government would protect every loyalist.” Since the strike leadership failed to effectively combat this Government propaganda it resulted in a minority of the more backward elements remaining at work. Sufficient, it proved, to form a nucleus around which volunteer labor could be organised to break the strike.

On August 8 the “Case of the Loco, Enginedrivers, Firemen and Cleaners’ Association” was published by the Secretary. This document, among other things, reveals how ill-founded were the Government’s charges that the union leaders were bent upon fomenting “bloody revolution.” The highly respectable, staid and law-abiding reformist leader of the Locomen’s Association literally bristles with indignation as he hotly refutes the implication of Fuller that he and his colleagues are not staunch supporters and loyal defenders of the capitalist regime.

“I would like to say deliberately,” he says, “that the statement so monotonously repeated for specific purposes, that our fight is against the Government as a Government, is entirely wrong. We merely encounter the Government on industrial ground. We are disputing with them and are prepared to treat with them as employers of labor. We clearly recognise that they control the general destinies of the country, and to assert that we are actuated by a revolutionary spirit or that we desire to usurp the functions of the Government is positively absurd ...

“For months my Executive has been faced with the spirit of unrest and discontent. Personally, I have used my hours of recreation for the purpose of allaying the troubles which were so evident.”

The statement then goes on to list some of the major causes of discontent among drivers, firemen and cleaners, including the “Stand-back” principle, under which men ordered to report for work at 4 a.m. may be told to stand-back to 6 a.m. before starting, without being paid for waiting time; “Broken-shifts,” again without any payment for the time men are kept waiting around in country depots; “Short time,” some men being given only nine or ten shifts per fortnight; and “Discipline,” which was far too harsh; men could he dismissed with no right of appeal. Locomen had been trying for years to have these grievances rectified, their secretary stated, but the Commissioner had consistently turned a deaf ear to their complaints. This left them no option other than to join in the strike. A concluding and most significant phrase refers to the card system as “A spark that fell into a cauldron of seething discontent and industrial impatience.”

The most important event on this day, Wednesday, August 8, was the deputation to Cabinet of representatives of the Colliery Employees’ Federation, Coal Lumpers, Waterside Workers, Trolley and Draymen, Seamen’s Union, Meat Industry, Gas Workers and the Australian Workers’ Union. The spokesman for the deputation, A. C. Willis, told the Acting Premier that:

“Matters have reached a stage where it is thought by those in charge of the dispute that other unions should be called on to declare their attitude. We therefore met them today. We quite realise the gravity of the situation and are anxious to do something to bring the dispute to a satisfactory conclusion. We have no wish to discuss the merits of the dispute. Since it is now effecting others we think even at this eleventh hour we can put a proposition that will help you out of the difficulty. We suggest as a basis for settlement that:

1. The State Government ask Edmunds J. to act as arbitrator and to enquire into the whole grievance.

2. In the meantime the Card System to be discontinued.

3. That on Edmunds J. being appointed all employees return to work, or alternatively the enquiry be held while the men are still out. The strike in the meantime to be no further extended.

“We feel our responsibility as much as you do and if an honourable understanding can be reached even now, what threatens to be a great national calamity can be averted. You know as well as we do that unless something is done the mining and other unions will be involved in a few days. We want to avoid that. That is the reason we are here tonight. We are not here to threaten at all.”

Herein we are given another example of how far the minds of labor leaders at the time were dominated by bourgeois philosophy. The idea of a general strike was that it constituted a “great national calamity,” ranking with droughts, floods, bushfires and the blow-fly pest. Far from having any notions of extending the strike and converting it into a political struggle, the union leaders were most anxious to limit its scope and confine it within narrow economic bounds. The Government and not the union leaders were responsible for the manner in which the dispute spread. Had they wished they could quite easily have terminated the conflict at this stage. But having once embarked upon the struggle it seems that the Government was determined to “teach the unions a lesson they’d never forget.” After no more than ten minutes private discussion with Cabinet, Fuller curtly informed the deputation that there was “nothing doing” and that the strikers had better return to work as quickly as possible.

On August 9 the ranks of the strikers increased to 45,000, when coal miners, waterside workers and more trolley and draymen ceased work. But the Railway Commissioner was able to go on extending his emergency service. Seventy-four trains ran into the metropolitan area on this day including the Melbourne express and several important mail trains. Eight goods trains also left Sydney for various country destinations. There was also a progressive expansion of the City tram service throughout the day. At 8 a.m. there were 84 trams on the road. By 3 p.m. the number had increased to 175, or 56% of the normal service.

An important statement was issued by Claude Thompson, Secretary of the Amalgamated Railway and Tramway Service Association, setting out the reasons why this organisation had thrown in its lot with the strikers.

“The present industrial upheaval,” he declared, “which occurred in connection with the introduction of the card system has brought under public notice other grievances of a serious character. It is true that the initial source of the trouble was the card system, but the whole trouble has wider foundations.

It is the outcome of a whole series of pin-pricking and goading on the part of the Railway Commissioners. Had the dispute been confined to the card system there would have been no general cessation of work of members except those in railway and tramway workshops. But while this dispute was proceeding the doors of the Arbitration Court were banged in the face of this union. For upwards of three years our members have been groaning under an oppressive system. After long years of waiting we got an Award from the Court which was not satisfactory.

The Association tried to appeal but was thrown out of Court because some members were on strike. On the same day the Commissioner Was allowed to appeal. The Court applied the “Margin and Textile Judgement” (apparently the law of diminishing rates above the minimum. E.W.C.) and practically all men in per. way and inter locking sections had their wages reduced automatically. When this was known the indignation of members reached boiling point and it became impossible to restrain it. There were incessant demands for throwing into the melting pot our grievances with those endured by other railwaymen. The Amalgamated men will not return to work until the recent Award is withdrawn and our grievances rectified ..."

The facts set out in this statement, taken in conjunction with those contained in the Locomen’s Manifesto, create the impression that guerilla warfare between the Railway Commissioner and the Unions had been raging for some time. A climax was pending and the card system served as an excuse for both sides to seek a final showdown. The attitude of the Commissioner and the Government throughout seems to have been deliberately provocative. They evidently felt sure of their ground and were confident in their power to inflict a decisive defeat upon the unions. In all probability, however, they underestimated the great depth of the general discontent prevailing and didn’t foresee the extent to which the railway strike would find support in outside undertakings. But once having cast down the gauntlet there was no alternative but to go through with the fight to the bitter end. The unions on their part, having accepted the challenge, found themselves compelled to do likewise.

The Defence Committee issued a statement in reply to Fuller’s threat to enrol volunteer labourers. It further exposed the utter bankruptcy of reformist officialdom.

“The Defence Committee has carefully considered Mr. Fuller’s proclamation,” it declared. “It is a mixture of bluff, mis-statement and intimidation. The Commissioner cannot fill the places of 20,000 highly skilled workmen now on strike. Any attempt to introduce scab labour will result in disastrous injury to highly-priced machinery.

“The Government has no power to override the rights already conferred on railwaymen and tramwaymen, which are specifically protected by Act of Parliament and judgments of the Arbitration Court.